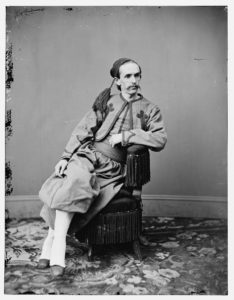

John Surratt, Lincoln assassination conspirator, in his Papal Zouave uniform. (Library of Congress)

On Feb. 19, 1867, the American gunboat Swatara returned to the Washington Navy Yard after a months-long trip to the Middle East. Out stepped a young man in a bizarre but filthy uniform and shackles. His name was John Harrison Surratt, and he was the most wanted man in the entire world.

Two years earlier, Surratt had been a Confederate spy. The Maryland native had conspired with John Wilkes Booth and others to kidnap President Abraham Lincoln in a desperate bid to reverse the tide of the Civil War. But the plot had failed, and on April 14, 1865, Booth instead fatally shot Lincoln inside Ford’s Theatre. Newspapers across the country featured photos of Booth and Surratt under the headline “Assassins!”

Booth was hunted down and killed in a burning barn in Virginia. Eight of his alleged co-conspirators — including Surratt’s mother, Mary — were arrested, quickly tried by a military commission and found guilty. But John Surratt was nowhere to be found. For nearly two years, he lived in hiding, wore disguises and watched as his mother and friends were hanged. Surratt traveled to half a dozen countries on three continents, and even joined the Pope’s personal army.

Surratt’s remarkable tale is a footnote in the sweeping history of the Civil War, often overshadowed by Booth’s infamous act. One hundred and fifty years ago, however, Surratt’s trial threatened to expose ties between the Confederacy and Lincoln’s assassination. Instead, it showed that the newly reunited country was ready to move on.

The material above is excerpted from the Washington Post’s “Retropolis” feature about history in a column by Michael E. Miller ‘Assassins!’: A Confederate spy was accused of helping kill Abraham Lincoln. Then he vanished, published on April 13, 2017.